THE ART OF BRINGING WOOD TO SPEAK

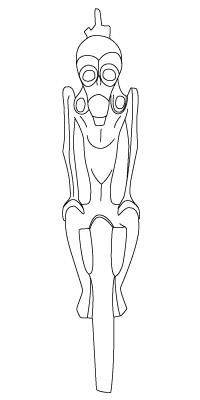

Which were the Dayak artists’ gestures and technics? Traceology and archaeo dendrometry unveils the wood’s secrets!

Détail of an archéological wood of Bornéo, Shorea sp., dated C14 14th century . Photos & copyright Jean-François Chavanne

The disciplines which study the wood, whether it be timber or carved by mankind, are named from the prefix of Greek origin Dendron which means “tree”, followed by a radical showing the method: dendrochronology to obtain dates next to nearly a year near; morphology dendro for the study of the tree’s dark circles which put in evidence, through the tree’s growing variations, the recent or distant climate perturbations; dendro origin to identify the wood’s geographical origins; dendrometry to measure the countable physical characteristics and dendrotypology to be able to classify the wood according to parameters.

Concerning handcrafted archeological wood having stayed underground or in the water and whatever be their final use (furniture, framework, piece of art, etc…), the archaeo dendrometry is going to literally read the wood’s history and provide information as much as on its environment as on the way it has been worked upon during its making. The ligneous state and the wood’s anisotropic attributes allow one to make out the different stages of the wood with artifact and to identify the carving marks among other traces left. The cuts, the removals, the absence of material, the wears, give this discipline’s scientists the necessary elements to “trace” the studied object’s history, and this whatever be its age.

L’étude archéo-dendrométrique des utilisations du bois dans l’immobilier (charpentes, pans de bois) et le mobilier (objets, oeuvres d’art) permet non seulement de révéler le bois comme traceur chronologique et écologique mais également économique, culturel et même politique et religieux au travers de l’étude des techniques de fabrication de ces structures. (1)

-Catherine Lavier, Christine Locatelli, Didier Pousset. De l'artefact en bois à la nature forestière : quelques histoires parlantes. Revue Forestière Française. Le bois de ses origines à nos jours. 2004.

This non-intrusive methodology gathers data without harming the matter and is regularly executed on excavated materials, on site or in a laboratory, by public or private operators, to collect vital information that allow to contextualize the artifacts within their culture and their environment. “Archeologic wood, well conserved in the earth or in the water, reaches us with a lot of information on its past. Archaeo-dendrometric studies gives us information on the tools used, the movements performed by the craftsman or the artist, moreover if this one was right or left handed. The wood’s morphology can also indicate which part of the tree the artifact’s wood was taken from, which was the working method used and its relation with the climatic environment. The wood reveals itself to be also a chronological and ecological tracer as well as an economic, cultural and even political and religious tracer throughout the studies of the fabrication technics of these structures. The wood reflects the society’s wills, compelling or not, but also the consequences of the mechanical obligations of the materials at their disposition”.

An inhabitant of the Apo-Kayan arriving at his village with a ceremonial dayak post emerged from a river. Photo Anton.2006. Copyright Bertrand Claude.

The xylologic and archaeo-dendrometric studies of the scientific laboratory Xylodata were done in September 2008, that means a few months after its emersion from one of Borneo’s rivers by two ancient wood specialists of international reputation. Victoria Asensi Amoros, PhD in archeology, Egyptologist, micrographe expert in woods issued from the University of Paris 6 and lecturer at the National Natural History Museum, and Catherine Lavier, research engineer at the CNRS, specialist in archaeo-dendrometry and dendrochronology in the Molecular and Structural Archeology Laboratory of the University of Pierre and Marie Curie in Paris who worked many years at the Research and Restauration Center of France’s Museum ( Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musées de France), the CRMF of the Mix Research Unity of the National Scientific Research Center. Their study gives innovating information on the used materials, the shaping techniques and their interaction with the tropical climate’s environment.

THE STONE-WOOD

This essence (Shorea, group Balau, family Dipterocarpaceae) particularly heavy and resistant, has been identified by Tom Harrisson on archeological material coming from Borneo.

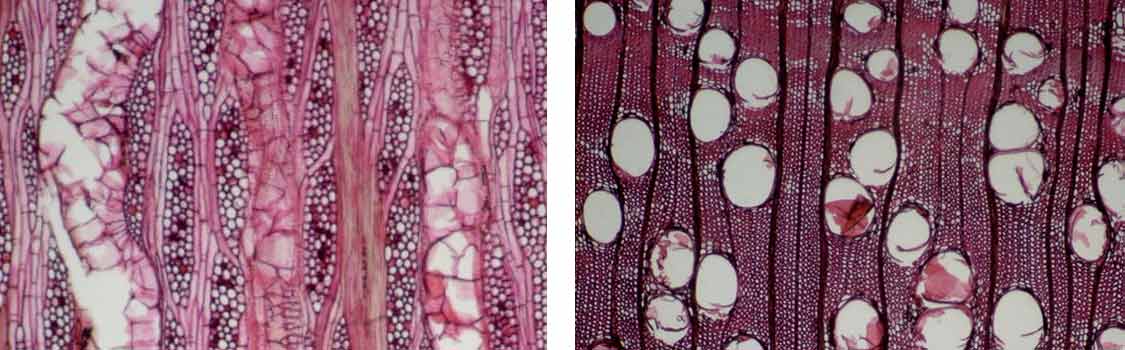

The wood used was identified as being Shorea, from the Balau group, from the Dipterocarpaceae family which is found in a geographical area that covers all South-East Asia and particularly Malesia, Sumatra and Borneo. This essence which is particularly heavy and resistant, has been identified by Tom Harrisson on archeological material coming from Borneo. The results of the xylologic analysis he has done on at least ten artifacts coming from different excavations held in Borneo in the 1950’s, have been published in “Prehistoric Wood from Brunei, Borneo” by Brunei Museum in 1974. One of them, in Shorea wood, is dated through C14 to be from 940 A.D. The kind Shorea includes no less than 200 species of trees and one of them, the Selangan Batu (batu=stone) is mentioned by Antonio Guerreiro in the “general wood classification” catalogue p. 78 published in 2008, as being one of Borneo’s carvers favorite essence.

Microscopic views of a sample of Shorea sp.. Left, tangential cutting. Right, cross section. Courtesy Xylodata.

The carving of this piece of art has required an original log of an average of 60 cm diameter and a minimum length of 210 cm. The average density for the Shorea being of an estimated 0,85g/cm3, the calculation of the weight of the chunk of wood from the tree still standing gives a result which is near to 2 tons! This first data brings the first question around the logistic put together for this operation. After the tree being felled and pruned, was it carved where it was cut down and then transported to the village? Not unless the artist had roughen out his project on the spot so as to finish it off after, once in the village? Or better still, was the chosen tree in the village’s near proximity? Up to today, we do not dispose of elements allowing us to favor one or the other of these scenarios. Nevertheless, this questioning left without answers concerns most of the monumental sculptures of Borneo.

la punta dell’albero, ovvero la cima del tronco (hujung kayu), costituirà la parte cacuminale del pezzo di legno una volta terminato il lavoro, sia su un piano verticale, (palo, statua), (….) contrapposta alla base del tronco (pangkal kayu) che gli si opporrà diametralmente.(2)

-Antonio Guerreiro. Patong, la grande scultura dei popoli del Borneo.Città di Lugano, Museo delle Culture. 2008.

Two ethnological informations are given to us in Dr Victoria Asensis Amoros’ and Catherine Lavier’s report. The first one comes from the direction in which are situated the knots found on the sculpture which indicate that the carvings were made respecting how the tree was standing: head/crown’s side and feet/ roots’ side. This corroborates the observations reported by Antonio Guerreiro in the here above mentioned publication which explains that, in the Dayak tradition and in general Austronesian tradition, the carving of ritual woods must strictly respect the polarity base/tip (pangkal kayu/hujung kayu), that is to say the equivalent of root/crown for vertical statuary. This rule must be scrupulously respected as well as must be kept the distinction of the used essences, based on their hardness, and the dimensions of the sculptures done so as to correspond to a hierarchical notion within the tribe.

HEAD TO CROWN, FEET TO ROOT

View of the canopy of a Dipterocarpaceae forest in Borneo, Indonésia. Copyright Donald O'Hare. Courtesy jezohare.com

This set of informations – choice of a hard essence, respect of the traditional polarity sky-earth / head-feet – testify that this monumental sculpture has been erected according to strict rules within a traditional ritual which has now disappeared.

The second information allows to situate the location of the log within the tree thanks to its knots’ orientation : where the crown is, starting point of the antlers. The knot situated on the right hip (fig. 7), starting point of the main slot which goes across the back up to the left shoulder, could be the one nearest to the trunk’s heart, but that does not enable us to evaluate the trunk’s diameter. Apart from its technical aspect, this data certainly presents an ethnographic character. In an animistic society, where each natural element is a spirit’s sanctuary, the choice of the tree from which is going to emerge a sculpture is issud from a thought which inscribes itself in a traditional ritual. Just as for the carver it is a question of respecting the polarity crown-sky/roots-ground, deciding to carve a piece of art of this size at the level of the tree’s crown results of a conscious decision. On a purely technical point of view, it is easier for a sculptor to use the main bole of the tree that does not have any branches. The rainforest’s trees, among which is the Shorea, carry their crown at dozens of meters high. Well now, this part of the tree is very little employed as wood for craftwork because its exploiting is rendered difficult by the presence of knots and curved and sinuous branches. Choosing the crown is then very probably a significate act, the sense of which has not reached us. Let us as well remember that the Shorea provides a resin of great quality called Damar used among other things to seal funerary jars and its nuts (Engkabang) with known virtues were used during Dayak rituals, funerary or others. This set of informations – choice of a hard essence, respect of the traditional polarity sky-earth/head-feet – testify that this monumental sculpture has been erected according to strict rules within a traditional ritual which has now disappeared. Arisen from the depths of a river, this statue reveals the dreams and the evaporated beliefs of a little group of humans from the forest. She is the sole fragment of a human memory now disappeared.

Detail of the right hip, starting point of the large dorsal fissure. Photos & copyright Jean-François Chavanne

SPLITS & CRACKS

This retraction phenomenon, one of the most spectacular aspects of which is this formation of scales on the surface, proves that the wood has been dried naturally in situ after the piece of art being carved..

-Catherine Lavier, Dr. Victoria Asensis Amoros.Observations tracéologiques et archéodendrométriques. Xylodata. 2008-

The archeological wood goes through time carrying the traces of its history. The observation and the study of these informations, under the effects of mechanic and climate pression, reveals its past. This study highlights the fact that Shorea, a solid and resistant wood, has been little affected by the hard tropical climate of Borneo or living organisms’ attacks. The equatorial forest’s diluvian pouring rains have greatly furrowed its surface but it has remained dense and heavy. The areas which are structurally fragile do not show any decreasing and the wood used is still very resistant. The fissures which can be observed are the result of this great solidity, which renders it brittle when under the ceaseless assaults of rains, humidity and beaming sun. The visible scales on different spots are also linked to this essence’s attributes. Issued from the loss of its water, they mold into the form given by the sculptor. The loss of its structural water, above 30%, expresses itself by the withdrawal of its timber, until it has reached its hygroscopic balance. These splits, more or less large, are stimulated by branches’ observed starting points, as well as by a gall on the right shoulder. This retraction phenomenon, one of the most spectacular aspects of which is this formation of scales on the surface, proves that the wood has been dried naturally in situ after the piece of art being carved.

SCALES

CRACKS AND RAVINATIONS

MACROSCOPIC OBSERVATIONS

rapport archéo-dendrométrique, 2008 - Catherine Lavier, Victoria Asensis Amoros

Details. Left to right. Skull right back. Profile left chest. Head left side. Photos & copyright Jean-François Chavanne

TOOLS & CARBONIZATION

Concerning the wood, the technological study allows one to understand an object’s fabrication through the examination of its manufacturing, shaping, how it was used and its wear-out signs, all which are possible to be restituted starting from the tree when it was still in the forest up to the exposed object in a showcase..

In the 1930’s, the Russian prehistorian Sergueï Semenov (1898-1978) elaborates a method to study the marks left by the use of Paleolithic flint tools which is based on the examination of the stigmas, particularly at a microscopic scale, left by its use or the shaping, so as to identify a material’s or an action’s signature. Concerning the wood, the technological study allows one to understand an object’s fabrication through the examination of its manufacturing, shaping, how it was used and its wear-out signs, all which are possible to be restituted starting from the tree when it was still in the forest up to the exposed object in a showcase. It will only be when the works of Sergueï Semenov have been at last translated and published in 1964 in a book entitled “Prehistoric technology” that the investigation field will start to organize itself. This technology will take off in the 1980’s, particularly within the French scientific community. Developed at first for stone tools, it is going to be progressively applied to other materials such as bones, ivory, cervids’ woods, woods and metals. The original works of Patricia Anderson, research director at CNRS followed by Menasanch’s studies on non-sharp tools have showed that the economical and sociological interpretation is within reach with traceology. Now, through the observation of traces, wear-out marks and traces of use, the method elaborated by Sergueï Semenov today allows one, through microscopic and macroscopic observations, to identify the tools used, the manufacturing steps and the expertise used. The museums, among which the Quai Branly, regularly appeal to these technics to look for information or confirm information on the wooden objects in their collected pieces.

More generally, this study confirms that the traces of cuts and shaping observed are the result of human actions, these objects having been used and worn out, although these last marks are more important and have a tendency to cover the others..

-Catherine Lavier, Dr. Victoria Asensis Amoros.Observations tracéologiques et archéodendrométriques. Xylodata. 2008-

The macroscopic observations done on this statue from Borneo reveal that, although its wood is very hard and that it is difficult to carve, the basic features, although very much subdued by the climate’s environment, are simple and indicate, by their balance, a total mastering of the material by the artist. The trunk has undergone distortions due to the branches through an equilibrium reaction of the tree. It is a natural aspect. A greenish color on certain parts of the sculpture indicates the presence of organic elements of local origin, but no mildew, moss or lichen, are to be observed. More generally, this study confirms that the traces of cuts and shaping observed are the result of human actions, these objects having been used and worn out, although these last marks are more important and have a tendency to cover the others.

Left to right. Stigma of combustion. Right Shoulder and Lower Break. Photos & copyright Jean-François Chavanne

These carbonaceous marks (...) could be the result of the use of flaming torches on an area of devotion where was standing the sculpture.

-Catherine Lavier, Dr. Victoria Asensis Amoros.Observations tracéologiques et archéodendrométriques. Xylodata. 2008-

Traces of carbonization are observable at the foot of the sculpture, next to an open split situated on the inferior part, but they are not linked to fires, because in that case the traces would have covered a more important surface. They are not either linked to any slow controlled combustion, used for example to harden the wood or to operate a chopping of the trunk, or even to a slash-and-burn technique. These carbonaceous marks, restricted in size and deepness, are the results of a slow consummation with nearly no flame diffusion. They could be the result of the use of flaming torches on an area of devotion where was standing the sculpture. Similar traces are observed on statues within churches for example. Are they marks left after ceremonies or rituals? Impossible to say!

These traces carry a new ethnographic information. These carbonization marks where not technical or accidental, they make us think of the possibility of a proximity between the sculpture and a firepot, to give light for example. On the other hand, the combustion stigma situated at the level of the right shoulder corresponds to consumed wood. The residues of branches, extracted for one, cut for the other one, hampered the sculptor’s work. These charcoal clues, visible at the surface, indicate a possible use of a slow combustion fire made out of standing trees, a kind of roasting which consumes the matter until it is possible to extract from it the wanted element. All the combustion traces deliver a novel information on the sculptor’s work, and the use of such a sculpture by the tribe, the village, which produced it. The mastering of the fire by the artist during the elaboration of his work, ceremonies or night rituals in an environment nearby the hampatong?

And the authors of this study to conclude in these terms: “Up to this day, too little archaeo dendrometric analyses have been made on sculptures from Borneo to be able to give the first elements allowing to give answers corresponding to these observations.” These data are now available and ready to be confronted to new studiess.

1. The archaeo-dendrometric study of uses of wood in structures and furnitures (objects, works of art, etc.) not only helps reveal wood as chronological and environmental tracer, but also economic, cultural and even political and religious through the study of manufacturing techniques these structures.

2. The top of the tree, or top of the trunk, forms the top part of the woodwork once the work is completed, on a vertical plane (pole, statue), (... ..), as opposed to the base of the trunk which is diametrically opposed. Antonio Guerreiro, Patong, la grande scultura dei popoli del Borneo.Città di Lugano, Museo delle Culture. 2008. traduction BC.